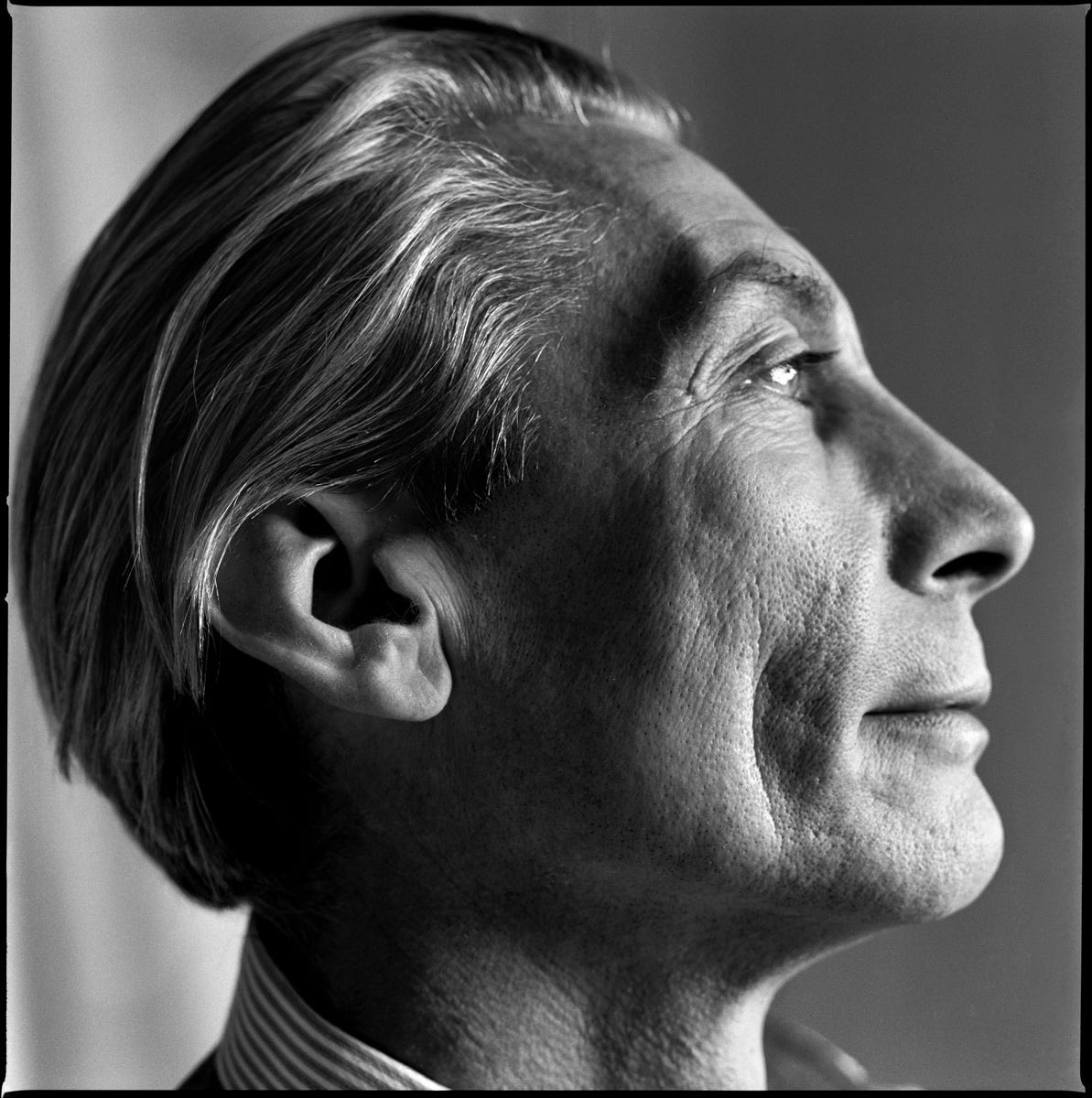

Jill Furmanovsky, my Rock Photos

“Rock chose me. When you realize you have captured the moment, you experience a great emotion.”

Half a century of photos that captured the moment of rock. For more than 50 years Jill Furmanovsky has been photographing music history. Her work is a very long photo album where we find shots of Pink Floyd, Bob Marley, Oasis, The Police, Sinead O'Connor, Billie Eilish, Amy Winehouse. Just to mention a few names.

A true legend of rock photography Jill Furmanovsky, recently awarded Legend of the Year at the So.Co Image of Music Awards, who at 70 (I will be 71 in Sept 2024), retains the same enthusiasm, passion for art, music and photography as she did when she started at 18, photographing, almost by accident, her first concert at London's Rainbow Theatre.

She welcomes us on a videocall to her London home, and immediately our attention falls on a photo behind her. "Would you like to see it? You know I think it's an incredible image.” Jill shows us a beautiful print of a very young Paul McCartney seen through a net-curtained window sitting alone in a garden playing his guitar. The family washing can be seen is hanging on a washing line. "His brother, Mike, took it when Paul was a boy. Besides taking pictures I love collecting pictures." It is one of her passions, along with her grandchildren and travel, although the camera, she says with a smile, does not leave her too much free time.

Tell us something about your home country. We read that you were born in Zimbabwe. Have you ever had a chance to return there? What memories do you have of your home country?

It’s a question with good timing because there’s a documentary being made about my work as a photographer. It starts in 1953 when I was born in a small town called Bulawayo in what was then Rhodesia (the name by which Zimbabwe was referred to before 1980.). I went back and looked at old family photographs, mostly taken by my father of the family, mainly my brother and I. My dad was an architect by profession, but he was also an excellent amateur photographer. We even had a darkroom in the house. Taking pictures, listening to jazz, and also playing guitar were his hobbies.

Looking at old pictures you immediately, see details that take you back to your roots, remembering that you did not come from nowhere. For various reasons I have not been back to my home country since 1992, although I was in South Africa more recently where my family and I used to spend vacations when I was a child.

Born in Africa but raised in London. Do you feel more African or British?

I felt like a foreigner for many years. When I came to the UK aged 11 in 1965, I was uprooted from my daily small-town life where I enjoyed a lot of freedom. I rode my bicycle around the streets and went to play in the bush. I experienced an African childhood, although always of European background, not indigenous I mean. Yet I was left with a passion for Africa, and at a certain point in my career I had the opportunity to do a journalistic and photographic project dedicated to the ANC (African National Congress ed.), immortalizing Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and many others. And for me it was like giving back to them a sense of gratitude, of thankfulness.

As someone born in Africa but then raised in London, what are your thoughts on the intense debate on the issue of colonization, which is also affecting the world of photography? In our interview with the Director of World Press Photo, Joumana El Zein Khoury emphasized the need to move beyond and beyond the Western point of view alone, embracing that of other countries and cultures.

I had a chance to read the interview with Joumana and found it very interesting. My old school atlas reflects that In the mid-1950’s the continent of Africa was almost entirely colonial - British, Belgian, German and Portuguese mainly. Today that map is very different and still changing but only in the last few years have we begun to reflect on all the consequences of colonialism because 50 to 100 years have passed. In the face of this recent awareness, we have begun to remedy it, at least in a small ways but there is a long way to go.

I feel the same bewilderment, on a smaller scale standing in front of my vast photographic archive. It feels like an almost impossible mission to absorb everything I've photographed over more than 50 years, and I’m still shooting! I realised recently that I won’t have enough years left in my lifetime to see it all, so the next generation will have to sift through it and evaluate its relevance. Hopefully it will inspire, because the Rock & Roll era was a particularly free and creative time for young people.

For bands and artists whose careers took off like a comet, Oasis for example, fame happened so fast and so intensely, I don’t think they had time to digest what was happening to them.

Can you tell us how you got into photography, what sparked the spark, particularly for the rock-related one?

I confess that it was a singular coincidence. In 1972, I was 18 years old, attending art school. In those years, in the UK, photography was not considered an art that you studied in an art school. There were courses in photography offered by technical colleges, men in white lab coats (!) and some postgraduate courses, such as those at the Royal College of Art, which offered photography and cinematography but at my college (The Central School of Art and Design) it was service department for the various degree courses.

Students studying fine art, sculpture, graphic design, theatre design or ceramics for example, were required to take a two-week photography course in order to photograph their work. However, teaching the classes were professional photographers, such as Jürgen Schadeberg (1931 - 2020), one of South Africa's greatest photojournalists, and Ian Hessenberg, a fashion photographer. They were inspiring to me.

At the end of the first week they put a camera in our hands with which to go around taking shots on the weekend. And I went to the Rainbow Theatre to photograph the band ‘Yes’. At first I tried to shoot from the balcony, but then I noticed some photographers in the front isle, and I thought to myself, perhaps people will think I'm a professional if I crouch next to them. No one stopped me and I started shooting, not really knowing what I was doing. Unbelievably, two guys who were working at the Rainbow as photographers told me they had to leave to make a film and offered me to take their place.

I wasn't going to earn anything more than expenses, but I was given complete access to the concerts. On Monday I went back to college and told the staff that I had been taken on as the Rainbow photographer. I then stayed at college till I got a degree in graphic design, but at night and weekends I was a rock and roll photographer. You could almost say that rock chose me.

Which are the difficulties associated with this type of photography? What is your approach ? Do you study beforehand ? Do you improvise on the spot?

Working with musicians is wonderful, really a privilege. Working in this field has been a constant learning curve. I had to proceed by trial and error. I don't know if this is something that is known in Italy, but in the UK there is a strong link between art schools and music. Up until the 1990’s even if your grades were low at school, you could get into art school with a good portfolio. So in my art college I found different musicians, like Joe Strummer, songwriter and guitarist of the Clash, and punk performer, Lene Lovich.

In general, I found myself moving in an environment made up mostly of self-taught people with no specific training. There was this atmosphere in the world of art and music of “you can do it,” which was accentuated during punk, where the phrase that recurred often was : “If you can play three chords, you can form a band.” And in this context I felt comfortable, finding many kindred spirits among musicians.

Technically what are the difficulties in taking such photos? How do you deal with them?

A lot has changed since I began. In the 1970s everything was photographed in black & white, and the cameras were obviously analog. I used to use a Pentax and then a Nikon. It was necessary to anticipate action, to focus, to find the right exposure. It was all manual, there was nothing automatic, however, you could stay for the whole show. You would slip into the pit before the band started playing and stay there for the whole concert. The more experienced photographers generally made sure they still had enough film in the middle of the show so they wouldn't miss the finale. Those with less experience could often run out of film earlier than expected, missing the best shots of the end of the concert. But at least the shows could be accessed. Of course there were difficulties, but nothing comparable to those of today.

Between the 1970s and 1980s I started taking journalistic assignments for the music press. It involved traveling with musicians and shooting fly-on-the-wall style, in black & white, mostly reportage. And it involved an additional learning curve, because you had to have a dialogue with the musicians, it wasn't like with concerts, where you don't talk to anybody. Then came the further challenge, that of colour, with the advent of The Face magazine in the 1980s. And most importantly, Annie Leibovitz appeared on the scene with her covers for Rolling Stone, and we had to, like, up our game, to shoot colour with studio lighting. The technical difficulties were compounded by the business aspects, managing the editors, etc., but that would be a really long talk.

But how do you catch the right moment, the fleeting moment? Does it click with the music, what happens?

It's really hard to define. I often experience frustration with technology and still don’t consider myself to be technically good, yet I have managed to catch the right moment often enough to encourage me to keep going. Often it's something you realize only later, at least that used to be the case with analogue photography because you only saw the results when the film was processed. With digital equipment it’s the opposite: in theory you could set up a camera to fire automatically at the stage and then go and get a cup of tea. When you come back you will have some good pictures even though you were absent. I still think that learning to see clearly, being able to anticipate action, to be aware of mood and to capture light, atmosphere, and dramatic moments is what makes the process of photography so intriguing, mysterious and magical. And I think the viewer somehow intuits this too.

Given your long experience as a rock photographer, do you still feel the adrenaline as much as you work, when you happen to photograph musicians, bands. Or is it not the same as it used to be?

I would like to answer by first saying this: I prefer to say I am a photographer, not a rock and roll photographer. The adrenaline, the energy you describe, comes from wanting to capture something – it’s an obsession that goes beyond rock and roll and is more related to our ancestors urge to hunt perhaps. During lockdown there was obviously not a lot of music to photograph, so I started shooting pictures of a family of foxes that lived in the garden I overlooked from a first floor flat. At dawn they would appear with their young and I was ready for action looking out of the window, still in my pyjamas with my long lenses wating for the show to begin. Taking those unpredictable images gave me the same charge that I feel when I photograph a live concert, because I was capturing something that fascinated me. Shooting can be a way of worshiping life/nature through a lens and when you realize you have captured a special moment, you experience a great emotion

After Covid I went back to photographing musicians, although I don't feel the need to chase every new artist now. However, if I see something that excites me, like last year at Glastonbury, when I saw the band, Gabriels playing on a side stage. I instantly fell in love with their music and had the urge to follow them. And when I say follow them, I mean literally. I heard that they were going to perform again in the city of Coventry, and how should I say it, I instantly found myself with camera in hand, ready to go. I took a train there on a Sunday afternoon, not telling anyone that I was going. Once there I talked my way into a sound-check, and the band then allowed me to take portraits of them as well as live pictures. I was thrilled. It was like being 18 again!

What can we say, wonderful. We have for you a question coming from Italian photographer Paolo Brillo, famous for his extraordinary shots dedicated to Bob Dylan. He asks if rock photography is still relevant considering the restrictions, the difficulties on accreditations, security. What do you think?

I am a big admirer of Paulo’s work. I think what he does is both relevant and important. All these modern restrictions – for example press photographers only being allowed to shoot the first 3 songs of a concert - have caused us to lose something. Paolo has a precise and sympathetic approach to his work. He knows where to sit in each venue for the best angle, and is capable of being invisible so he can shoot for the whole concert when all the other photographers have left. He is also a fan so his pictures express the communal passion of the audience. Also he doesn’t only shoot picture of the vintage maestros like Dylan and Neil Young, he also shoots newer talent like St. Vincent, Aldous Harding, and PJ Harvey.

Incidentally, I also chased Bob Dylan for a few years because I found his mature music and aging face really beautiful. I really love it, but maybe he won't like it that much - he prefers how he looked when he was young! (laughs Ed.) Paolo does this type of clandestine work better than I do now, and although it is nerve-wracking I think he has a lot of fun, as I did dodging the security look-outs. Each image becomes precious because the process is so difficult. Without Paolo’s contribution the history of rock would be poorer.

You have photographed many musicians and bands. Is there a curiosity, an anecdote, a curious and funny situation that you remember in particular?

With this question you put me on the spot, because I tend to enjoy everything I do. I do remember working with Oasis in Paris, though, and Liam was definitely tipsy. He had spent the night without touching the bed, and in the morning he was still at the bar, but we had to do a photo shoot. We went out and immediately we were chased by some paparazzi. Instead of doing the shots Liam kept chasing after girls on bicycles on the bridges. Noels was furious. So I told him to stand in one place, that we were going to shoot anyway with Liam running in and out of the shots, because he was running left and right. And I have to say that in the end the result was outstanding, I would say similar to those slightly wacky families photographed by Diane Arbus. We seemed to be in a kind of comedy, in a demented movie, where we sober people were trying to get it together with a definitely tipsy person. In the end, though, as I said, the results were really very positive.

And is there a group or artist you are most connected to?

Yes, with several artists I have worked for many years, and we have become friends. We meet not just to take pictures, but also to have tea and chat. For example, Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders, with whom I started working since 1977. A unique and brilliant artist. We did a lot of collaborative and experimental work in the studio especially in the 1990’s. I have also worked over many years with Noel Gallagher, David Gilmour and Nick Mason, the group Madness, and the greatly missed Sinead O’Connor. They are professional friends but it’s a precious gift.

Let's change the subject completely, with one last question, to touch on a very hot topic in the world of photography today, that of the use of artificial intelligence. What are your thoughts on this?

It's a question I've been asked a lot recently and I confess I feel a bit ignorant, because I'm not sure I fully understand how it works. I personally don't feel threatened by any technology, because they are basically tools. The more troubling issue, that of altering the truth is an issue that has always been quite problematic in photography, already with Photoshop, but it’s not new. Manipulation was also happening with analog. In Russia they used to cut ‘persosonas non grata’ out of official pictures, in Hollywood in the 1940’s negatives were airbrushed or manipulated in the darkroom. Manipulation has always existed. As a girl, when I was just starting my career as a photographer, I would look at war photography and wonder whom I could trust to tell the truth. In the work of photojournalist Don McCullin I sensed that there was something deeply honest about his work.

So certainly photographs can be cropped, taken out of context, and possibly altered, but I think it remains essential, as strange as it may sound to say today, to find a photographer you can trust.